|

|

The Earthquake of January 26, 2001 in Gujarat, India - A Reconnaissance Report and Identification of Priority Issues You

can download (size: 48 kb)

a PDF version of this document. (You must have a PDF viewer,

and you may obtain a free copy at the Adobe

Acrobat website). The

Bhuj Earthquake

INDEX 1. Introduction 3.

Impact of the Earthquake 4. Planning for Rehabilitation 5.

Long-term Issues for Rehabilitation and Mitigation Annex: Documentation on Earthquake Damage Photos

from the Reconnaissance Mission

This

is a reconnaissance report of the Bhuj earthquake that struck Kutch

and other districts in the western state of Gujarat, India on January

26, 2001. On behalf of the World Institute for Disaster Risk Management

(DRM), Krishna S. Vatsa joined a mission organized by the Earthquake

Engineering Research Institute, Oakland, CA and visited Gujarat

from February 4 to 12, 2001. The report provides a brief account

of the physical details of the earthquake. It also discusses the

human and economic impact of the earthquake. However, the main objective

of the report is to identify those issues, which are crucial for

long-term rehabilitation and mitigation. These issues are: (i) reconstruction

and development (ii) disaster management planning, (iii) emergency

communications, (iv) seismic rezoning, (v) seismic engineering,

(vi) building codes, (vii) microzonation, (viii) essential facilities,

(ix) critical infrastructure protection, and (x) disaster risk insurance.

The report provides the institutional and regulatory context for

each of these issues. The report also makes recommendations for

implementing appropriate action plans with respect to each of these

issues. The Government of Gujarat has commenced a large-scale rehabilitation

program with the financial assistance of the World Bank and the

Asian Development Bank. It will be necessary to address these long-term

issues in the course of the program implementation to reduce physical

and social vulnerability in the region. A rehabilitation program

encompassing these issues could be a great learning experience for

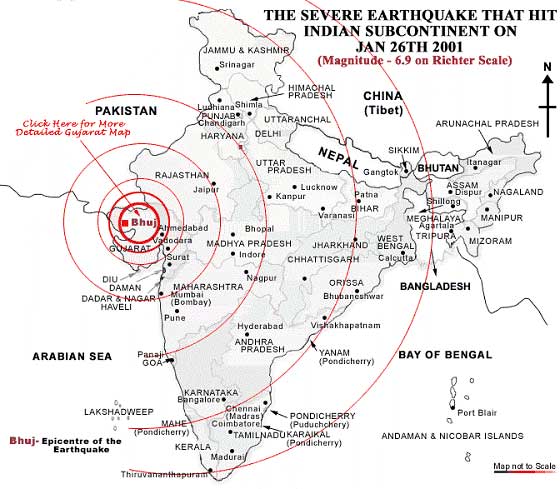

the rest of India and other developing countries. On January 26, 2001, an extremely severe earthquake struck the state of Gujarat in western India at 8.46 a.m. The earthquake devastated the district of Kutch in the northwestern part of the state, and many other districts of the state also suffered terrible human and property losses. The city of Ahmedabad, the commercial capital of Gujarat, which lies 300 kilometers from the epicenter of the earthquake, had a collapse of more than 70 high-rise residential buildings. It was the worst disaster to have struck India in the last 50 years. The

Kutch region forms a crucial geodynamic part of the western continental

margin of the Indian sub-continent, and falls in the seismically

active Zone-V outside the Himalayan seismic belt. It extends for

approximately 250 km (E-W) and 150 km (N-S) and is flanked by Nagar

Parkar Fault in the north and the Kathiawar Fault in the south.

The area bounded between these two faults comprises several E-W

trending major faults viz. Katrol Hill Fault, Kutch Mainland Fault,

Banni Fault, Island Belt Fault and Allah Bund Fault (Malik, et al,

2000).

Zone V, which includes Andaman & Nicobar Islands, all of North-Eastern India, parts of north-western Bihar, eastern sections of Uttaranchal, the Kangra Valley in Himachal Pradesh and the Rann of Kutchh in Gujarat, is the highest level of seismic hazard. Earthquakes with magnitudes in excess of 7.0 have occurred in these areas, and have had epicentral intensities higher than IX on modified Mercalli scale. The Rann of Kutch has experienced above normal levels of microseismicity throughout the past 200 years, and probably for many millennia. Altogether 56 earthquakes have struck the region with magnitude ranging between three and four, and about seven quakes of five and above (1819, 1845, 1846, 1856, 1869, 1956, and 2001), the two major ones being Allah Bund and Anjar in last two hundred years. A severe earthquake of magnitude 8.0 occurred in 1819 at Bhuj and this gave rise to an 80 km-long fault scarp, Allah Bund, a natural dam uplifted at its crest by 6.5 meters, on the northern edge of the Rann. The second biggest earthquake recorded was on July 21, 1956 in Anjar. Of a magnitude of 7.0, this earthquake killed about 700 people. Magnitude, Epicenter and Depth There

are varying interpretations about the magnitude and epicenter of

the earthquake. The India Meteorology Department (IMD), which has

a seismograph at Bhuj claimed that the magnitude was 6.9 on the

Richter scale; the Geological Survey of India (GSI) at its Jabalpur

observatory recorded the magnitude of 7.6. The US Geological Survey

(USGS), which has the largest network of seismographs and satellites

for observation, claimed that it was 7.9, but later revised it to

7.7. The India Meteorology Department explained this difference

by saying that the US and other foreign agencies calculated the

magnitude with surface waves as the basic input, whereas the IMD

figure was arrived at by using P waves, i.e. the calculation was

done on Local Magnitude (ML) and the Body Wave Magnitude (MB). The

updated USGS estimate M7.7 is the Energy or Moment magnitude, a

more reliable measure, particularly for large earthquakes. Initial reports from the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) on January 26, suggested that the epicenter was 23.6 degrees North and 69.8 degrees East which is near village Lodai, located some 20 to 25 km north-northeast of Bhuj. But the Geological Survey of India (GSI) puts the epicenter at 23.21 degrees north and 70.41 degrees east, about 76 km east of Bhuj or 100 km NNE of Jamnagar. However, the US Geological Survey (USGS) claimed that the epicenter was located at 23.4 degrees North and 70.32 degrees east and 110 km NNE of Jamnagar. The earthquake was a shallow-focus event. The USGS estimated the hypocenter at 23.6 km below the surface. The preliminary IMD estimate was of a 15 km. Depth. The University of Tokyo further revised this estimate to an even shallower depth of 10 km. However, the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) consortium and the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI), Hyderabad have confirmed the focal depth of the earthquake at 23.6 km. The

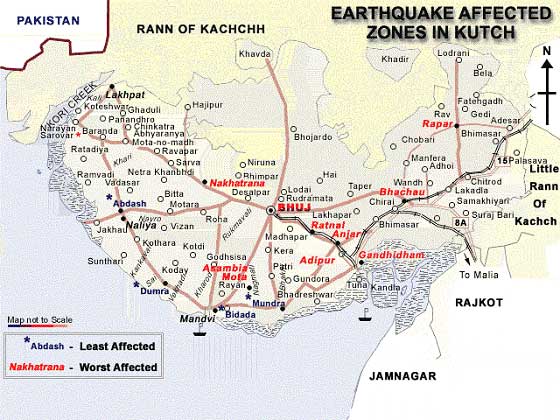

state of Gujarat was the worst hit by the earthquake. Bhuj, Bachhau,

Anjar, Rapar, and Gandhidham are the worst affected towns in the

district of Kutch, with Ahmedabad, Rajkot, Jamnagar and Patan also

severely affected. Though the impact of the earthquake was felt

in most of the states of India, there were no reports of significant

damages from other states. The

economic losses have been reported as follows:

The figure of US$4.5 billion provided by the Government of Gujarat is an approximate estimate. The precise estimate of economic losses due to the earthquake is yet to be established. 3.1. Damages to Infrastructure Among the first utilities to get knocked out by the quake was the communications network and power supply. There was an immediate loss of 3000 MW in the power grid. The tripping of a 220 KV line in Kutch resulted in total blackout of the whole district. Though the power supply in Ahmedabad was restored within a few minutes, it took as many as 15,000 Gujarat Electricity Board (GEB) personnel, 30 truck-loads of electricity poles, conductors, insulators and circuit breakers to restore power supply in Bhuj within two days. The damage in the electricity sector has been primarily in distribution. Most generation plants, which had initially tripped following the earthquake, started generating within 24 hours and the transmission systems too were up and running. It was, in fact, the damage caused to the sub-stations that held up power distribution to cities and villages. For instance, although Bhuj was supplied with 12 MW within a day's time, there were no takers for the power. Most of the water supply schemes failed because of the collapse of pump houses, and damage to the intake towers and pipelines. Water supply in the districts of Rajkot, Jamnagar and Surendranagar were also affected for similar reasons (The Economic Times, February 2, 2001). The

telecom building in Bhuj collapsed, with most of the telecom equipment

destroyed. Fibre-optic cables that gave connectivity to the district

of Kutch were also broken, resulting in isolation of the district

from the rest of the state. The

earthquake most seriously affected the Kandla port, the busiest

port in India, which caters to the hinterland of western, central

and northern India. It handles crucial imports of petroleum products,

crude oil and chemicals and exports of agricultural commodities. Roads

are relatively less affected. Aside from Surajbari bridge which

connects Gujarat to Kutch district, the national highways continued

to be functional. The earthquake substantially damaged the Surajbari

bridge, and for about 15 days only light commercial vehicles were

allowed over the bridge. More than 6000 Heavy Motor Vehicles (HMVs)

cross the Surajbari bridge everyday, which is the arterial connectivity

to the Kandla port. The bridge has been repaired and is now fully

functional. A new bridge connecting the Rann of Kutch to the national

highway, parallel to the Surajbari bridge, is also being commissioned

soon. Large-scale

petrochemicals and fertilizer plants in Gujarat emerged unscathed

through the earthquake. However, small-scale industry in Saurashtra

and Kutch has received a severe blow. More than 10,000 small and

medium industrial units have stopped production due to damage to

plants, factories and machinery. Diesel engine manufacturing and

machine and tools industry in Rajkot, ceramic units in Morbi and

There

are about 50,000 craftspersons who live and work in Bhuj, Anjar,

Rapar, Hodka, and surrounding villages, now completely devastated

by the earthquake. Kutch is nationally recognized for its rich quality

and variety of craftware. Many of the local craftspersons have died

in the earthquake. Besides, most of them lost their houses, workshops,

and tools, and are likely to face bleak days ahead. The loss of

their income opportunities due to loss of productive human and physical

assets in the Kutch and Saurashtra areas has been a major consequence

of the earthquake. People with little access to income-earning opportunities

are more vulnerable. Along with shelter, the restoration of livelihood

will be a priority for the rehabilitation program. 4. Planning for Rehabilitation The Government of Gujarat (GoG) has set up the Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority (GSDMA), which would implement the reconstruction and rehabilitation, with support from various other agencies in the quake-hit area. The GoG has announced four packages amounting to almost US $1 billion for reconstruction and economic rehabilitation for more than 300,000 families.

The

details of these rehabilitation packages are available on a web

site: www.gujaratindia.com.

The government has also announced US$2.5 million package to revive

small, medium and cottage industries. Damage assessment is still

going on, and the final shape of the rehabilitation program will

soon be firmed up. The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank have announced loans worth $300 million and $500 million respectively. The Government of Gujarat (GoG) has put forward a soft loan proposal of $1.5 billion to these two multilateral agencies. A number of other bilateral agencies including the European Union (EU), the Department for International Development (DFID), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) have also agreed to provide financial assistance for the rehabilitation program. The Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO) and the National Housing Bank (NHB), two major public sector institutions in India's housing sector, have also offered to provide financial assistance of US$400 million. While there has been no major impact on industrial units owned by major corporate groups, the leading chambers--the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) and the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industries (FICCI)-- have offered to adopt clusters of quake-ravaged villages for relief and long-term rehabilitation. A number of business groups such as Reliance, VSNL, Larsen & Toubro, Tata Steel, Coca-Cola, Essar and Videocon have decided to contribute to the rehabilitation program. Public sector industries too have provided huge donations for rehabilitation. A large number of NGOs, national and international, have participated in the relief operations. Many of these NGOs will gradually withdraw after the relief phase closes, as they do not have sufficient resources to participate in the reconstruction program, or do not have a long-term plan for local involvement. However, a number of larger NGOs will continue and contribute to the rehabilitation program. The government is actively seeking the NGOs to adopt villages for rehabilitation. It has announced a contribution of 50 per cent of the cost of rehabilitation, if a NGOs adopts the village for rehabilitation. Gujarat has a large number of prosperous expatriates settled abroad, and they will also contribute generously to the rehabilitation program. The prompt assistance declared by the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, a host of other donors and the Government of India has made it possible for the Government of Gujarat to mobilize adequate resources for the reconstruction program. The corporate sector and NGOs have also decided to contributed to the cost of reconstruction in a significant way. The cost of reconstruction would be funded through the following sources:

However,

it will be a great challenge to utilize the resources effectively

for rebuilding Gujarat. An earthquake rehabilitation program of

this magnitude requires careful planning and efficient management

structures. It will also be important to establish norms of accountability

and transparency in the implementation of the program. A strong

community orientation is also critical for the success of the program.

A reconstruction program is always a great opportunity for civic improvement. It regenerates the local economy due to massive investment over a short period of time. It can improve the quality of housing, and social and community infrastructure. It can also be a context for introducing mitigation and preparedness practices. People also tend to accept regulations better in these circumstances. In Gujarat, and also in the whole of the country, reconstruction programs should aim to realize these opportunities. This report identifies a number of issues that may be considered for rehabilitation and mitigation planning at the state and national level: 5.1. Reconstruction and Development Besides

engineering issues involved in reconstruction, a number of planning

and architectural issues are involved, which require a wide range

of consultations:

5.2. Disaster Management Planning Gujarat is a disaster-prone state. In the last few years, cyclones, floods, and droughts have repeatedly struck the state of Gujarat. The cyclone that struck Kandla in 1998 was particularly severe, causing deaths of more than 3,000 people. The frequency of disasters impressed upon the Government of Gujarat the importance of developing a comprehensive disaster management plan. However, the state could not mobilize resources for its implementation. After this earthquake, there is a consensus on capacity building in this area within the state and the country. The Government of Gujarat's renaming of the Earthquake Rehabilitation Authority as the Disaster Management Authority is symbolic of the importance it attaches to the disaster management system in the state. The state seems to have taken a broader approach to disaster management, by constituting this focal agency for dealing with all the hazards. Disaster management will be one of the most important components of the rehabilitation program supported by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. At the national level too, there are major initiatives under consideration. The Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee constituted a committee under his own chairmanship to suggest the necessary institutional and legislative measures required for aneffective and long-term disaster management strategy. A number of senior ministers and opposition leaders are members of this committee. The Government of India has decided to set up a National Center for Calamity Management. A High Powered Committee is also deliberating institutional changes in disaster management organization at the national level. In

Gujarat, a new disaster management system may address the following

priorities:

These initiatives require a great deal of planning, organization, and technical assistance. The disaster management system also requires a long-term financial commitment and resources for sustainability. It must therefore be implemented as a program separately from the reconstruction activities. India and the state of Gujarat can benefit from the experience of disaster management institutions and practices in the developed countries. It will also be useful to build collaboration with national and international research institutions and universities from abroad for the implementation of technical components of the disaster management plan. Applied research, technology transfer and training will be important components of a disaster management system. Of all the disaster management components, the emergency communications network is most crucial to emergency response. It ensures the flow of information, tracks emergency needs and helps in deployment of the emergency personnel. In this earthquake, the communication link with Bhuj could be restored only two days after the earthquake, and even after 10 full days, communication with Bhuj was not back to normal. The cellular network in the state failed. A large part of the state remained completely disconnected. The lack of communications impeded information flow and seriously affected relief operations. The situation was similar to the Orissa cyclone or the Marmara (Turkey) earthquake in 1999, where the disaster-affected areas were completely cut off from the rest of the country due to communications breakdown, impeding the rescue and relief efforts. These recent disasters clearly demonstrate that despite significant technological advances, the basic need for communications in extreme situation still remains-getting the right information at the right time. The tools now available to gather and deliver that information range from small, hand-held shortwave radio units to complex satellite systems, but, unfortunately, they are not always in the right place when disaster threatens or strikes and even, if they are, they do not provide the necessary information on vulnerable situations. It has created serious problems for those who rely on receiving the right information. A disaster

management plan must persuade for the creation of an efficient communications

infrastructure. A new telecom network may be designed connecting

the state capital to the lowest administrative units. The network

must be robust and dependable, and in case of a breakdown, alternative

arrangements must be activated. It could be a multi-tier network,

between different levels of administration-state to district, district

to Taluka, and further down to villages-- with combination of technologies.

Given that the cellular operators were the first to bring back their

services even in the most affected areas like Gandhidham and Bhuj,

the first choice of technology should be wireless. VHF and HF communication,

mobile radio trunking system, and wireless in local loop are some

of the technological alternatives. A great deal of applied research

is going on for the development of advanced versions of wireless

technology, and the new applications must be harnessed for building

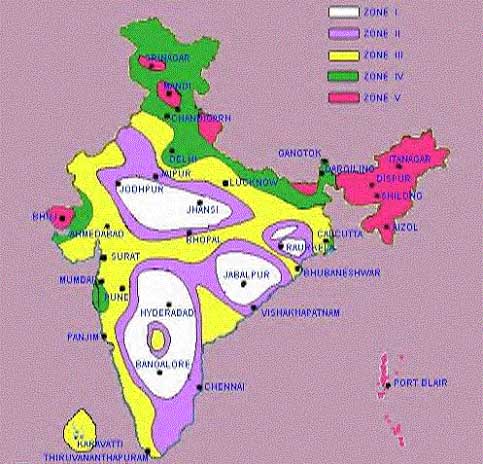

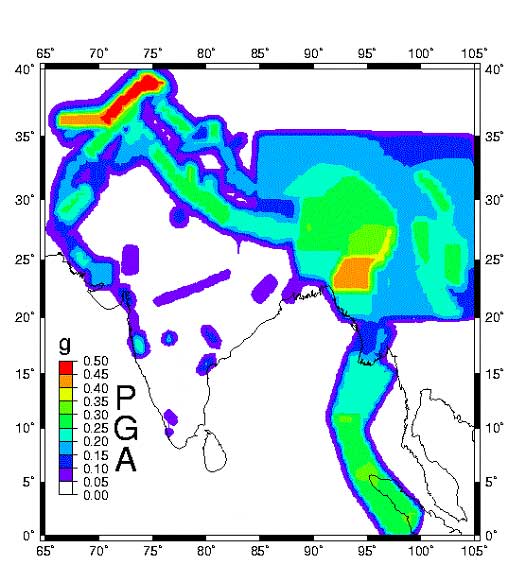

the communications network. (). The first national seismic hazard map of India was compiled by the Geological Survey of India (GSI) in 1935. A second national seismic hazard map was published in 1965, based primarily on earthquake epicentral and isoseismal maps published by the GSI. The

Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), which is the official agency for

publishing seismic hazard maps and codes in India, produced a six-zone

map in 1962, a seven zone map in 1966, and a five zone map in 1970

/ 1984 (Bhatia, et al., year not specified) The last of these maps

is accepted by all the national agencies currently valid; this map

was created based on the values of maximum Modified Mercalli intensities

observed in various parts of the country, in historic times.

The National Geophysical Research Institute, Hyderabad prepared this seismic hazard for the Indian region under the Global Seismic Hazard Assessment Program. These successive seismic zonation maps of India more closely represented known seismotectonic features without sacrificing the information obtained from earthquakes and from theoretical ground motion attenuation relationships. Another significant change in the revised maps was the abolition of zone zero, in recognition of the fact that it was not scientifically sound to depict any region of India to have the probability of an earthquake equal to zero. This had the desired effect of including some level of seismic provisions in the design of important structures. Khattri, et.al. (1984) prepared a probabilistic seismic hazard map of the Himalayas and adjoining areas that depicts contours of peak acceleration (in %g) with a 10% probability of exceedence in 50 years (Bhatia, et.al., year not specified). The present five-zone map, which is currently under revision, is as follows(2): Zone V (Very high risk quakes of magnitude 8 and greater): The entire North-east, including all the seven sister states, the Kutch district, parts of Himachal and Jammu & Kashmir, and the Andaman and Nicobar islands. These areas may experience Intensity IX and above on Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale. Zone IV (High risk quakes up to magnitude 7.9): Parts of the Northern belt starting from Jammu and Kashmir to Himachal Pradesh. Also including Delhi and parts of Haryana. The Koyna region of Maharashtra is also in this zone. These areas may experience to MM VIII. Zone III (Moderate earthquakes up to magnitude 6.9): A large part of the country stretching from the North including some parts of Rajasthan to the South through the Konkan coast, and also the Eastern parts of the country. A moderate risk zone associated with the intensity maximum of MM VII. Zone II and Zone I (Seismic Disturbances up to magnitude 4.9): These two zones are contiguous, covering parts of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, known as low risk earthquake zones. These areas may experience intensity MM VI . The Deccan Peninsula, known as the Stable Continental Region (SCR), has experienced a number of seismic disturbances in the recent past. In the last decade, two major earthquakes (Jabalpur, 1998), and Latur (1993) have occurred in this region. Bhuj too lay in the northern fringe of the stable continental region of India. Besides, in recent times, the country has experienced a series of earthquakes in other areas too: Bihar-Nepal (1988), Uttarkashi (1991), and Chamoli (1999). The frequency of earthquakes in India has necessitated a major re-assessment of its hazard potential on a national basis. A reconsideration of seismic zones of India has also become necessary in view of the growth in population and built environment across the country. The death toll from the Bhuj earthquake is almost 20 times higher than that of the 1819 earthquake(3), though both the earthquakes had a comparable magnitude. The rise in death toll is largely due to greater risk exposure on account of population growth in the Kutch district. Today, Delhi and Mumbai have become extremely vulnerable to seismic hazard, largely due to unregulated construction in these cities. The Koyna (1967) and Latur (1993) earthquakes followed by Jabalpur (1998) are the first few recorded earthquakes in the Stable Continental Region (SCR) in recent history. These represented a new phenomenon for the earthquake scientists, and underlined the need for reconsideration of the seismic zones of India. The BIS undertook a program to reconsider the seismic zone of India, but it is yet to be completed. In the meanwhile, an international seismic hazard map has been developed by Global Seismic Hazard Assessment Program (GSHAP). Seismic instrumentation in India has improved somewhat. The Indian Meteorological Department has upgraded 10 seismological observatories in peninsular India. A National Seismological Database Center and a Central Receiving Station have been established in New Delhi to receive, archive and analyze seismic data. At

the level of states too, specific programs have been undertaken

to study seismic hazards. The state of Maharashtra has prepared

a probabilistic seismic hazard map for the state. A similar exercise

is underway in Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal. The Government of

India has prepared a Vulnerability Atlas, which provides state-wise

details of housing stock, exposed to seismic hazard. In the earthquake, reinforced concrete (RC) buildings of ground floor plus four storys (G+4) and ground floor plus ten storeys and above (G+10) collapsed in Ahmedabad resulting in 746 causalities(4). In the city, only minor damage was observed in single, or two story short-period structures. Most of the damage was limited to G+4 through G+10 storey buildings having "soft story" at the ground floor. These buildings were not designed for lateral loads as required by IS 1893 (Zone III) and had, of course, no concept of ductile detailing for G+10 buildings as recommended in IS 13920 (Goyal, et al, 2001)(5). After the earthquake, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) deployed several teams of structural engineers, architects and senior civil engineers for a technical survey of all the damaged buildings. Each team came up with at least four to five buildings on an average, which would have to undergo major repairs before the occupants can move back in. These teams found apparent violations of the Indian Standard Code for Zone III. Building code violation was most prevalent in low-rise structures. The quality of concrete used in columns and building frames deviated from norms stipulated in the building codes. At

Bhuj, all of more than 100 multi-storey buildings that were built

over the last five years either collapsed, or, have been certified

as unsafe for habitation. Over the last two years, buildings of

up to eight floors had been approved in Bhuj without adequate technical

review. The building plans ---- are supposed to be approved as per

the IS building code for Zone V. However, there was little effort

at compliance with building codes on the part of the municipal authorities.

The builders cut cost, used more concrete and less steel. Staircases

were not integrated into buildings, which caused their collapse. The AMC has appointed the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT) as a nodal agency for providing technical services. However, the CEPT has not been able to find enough structural engineers. A great number of structural engineers will be required to deal with the reconstruction and retrofitting elsewhere in the state. In addition, damages to non-engineered buildings also need to be addressed on a large scale. One of the most important priorities of the reconstruction program will, therefore, be a capacity building program in seismic engineering at the state level. The program may include several components:

Seismic engineering must be the cornerstone of the rehabilitation program. This is an area where significant work has been done in the US, Japan and many developed countries. There are new technologies available, base isolation being one of the most important among them. In the beginning of the rehabilitation program, the following steps may be taken:

Engineering experts from India and abroad can work with the government, municipal corporations, engineering colleges, and research institutions on seismic engineering issues. A continuous education and training program can also be supported through a collaborative effort of earthquake engineering experts from abroad and the national institutions. The earthquake has dramatically demonstrated the need for compliance with building codes in the state. The Government is reviewing its existing building by-laws and regulations as per the provisions of the National Building Code, and till these regulations are finalized the state government has directed the municipal commissioners of all the six big cities not to approve building plans irrespective of their status. Non-compliance with building codes has been a serious issue for the Government of India too. The Ministry of Urban Development is considering introducing a national engineering law for the enforcement of building codes and certification of structural engineers. However, much more needs to be done. It is argued that though India has rigorous building codes, their enforcement is not mandatory. However, this is not entirely true. While there is no national law regarding the enforcement of building codes, these codes have been incorporated into the by-laws adopted by the municipal corporations. These by-laws require mandatory compliance with the building codes. However, the enforcement of these by-laws has been a serious problem due to the lack of trained engineers, poor monitoring of building practices, and corruption. It is also true that popular awareness about the importance of code compliance is very low. Unless these issues are appropriately addressed, the legal provisions will not be very effective in reducing risk. In rural areas, most of houses are non-engineered. Though there are standards for non-engineered houses, enforcing these codes will require a regulatory authority and technical guidance for a very large area, which is difficult to provide. A village council (panchayat) cannot be expected to enforce building codes. It requires enormous investment in setting up and sustaining a regulatory mechanism for the entire country. In

fact, the enforcement of building codes is not possible without

a national initiative. A national program comprising several measures

and incentives should be instituted to promote compliance with building

codes. National legislation for building codes, technical courses

in seismic engineering, a certification system for qualified structural

engineers, interaction with local governance structures, and public

awareness about the codes are the essential constituents of a national

earthquake mitigation program. It will be useful to commission a

multi-disciplinary study as a first step that could discuss the

state of compliance with building codes in India, and suggest relevant

measures to improve them. Local

geological and soil conditions contributed significantly to structural

failures. . Seismic microzonation maps, , are essential tools for effective earthquake and related land use planning. Seismic microzonation maps are detailed maps that identify the relative potential for ground failure or amplification during an earthquake in different areas. They may include one or more seismic characteristics (liquefaction, amplification, land sliding, tsunamis, subsidence). They are compiled from geological and geotechnical data and they reflect local site conditions It

is necessary to produce seismic microzonation maps, which have all

the above-mentioned details at the local level, following an earthquake,

before deciding on future locations for rebuilding. There is always

a possibility of geological hazards, at locations where the earlier

buildings have collapsed. All decisions regarding the land use planning

must be subject to the exercise of microzonation. It is important to undertake a detailed microzonation exercise for the settled areas of the Kutch region, which falls in Zone V. Besides, Ahmedabad and other major cities of Gujarat should also be included in this exercise. The microzonation program will help in deciding the location of new settlements, if it is undertaken along with the rehabilitation. In India, comprehensive microzonation has not been attempted in any part of the country, and so a beginning in Gujarat will be a very positive initiative in seismic mitigation. 5.8. Essential Facilities: schools, hospitals and public buildings Essential facilities are those buildings that support functions related to post-disaster emergency response and disaster management. These include state secretariat, district headquarters, police and fire stations, hospitals, potential shelters (including school buildings), and buildings that house emergency services. The unimpeded availability and functionality of these buildings immediately after a disaster is a top priority in disaster preparedness. It may be useful to develop a separate rehabilitation strategy for this group of buildings. In the case of these buildings, their public use and availability are far more important than the potential economic loss. A statewide retrofitting program for the buildings should be initiated. For example, in Ahmedabad, the office of the Municipal Corporation and the Collector must be retrofitted on a priority basis. Based on a rapid seismic appraisal of these buildings, a retrofitting solution can be developed. If it is not possible to include all the essential facilities, at least a few public buildings in every district of Gujarat may be selected on the criteria of functional criticality, predicted ground motions, and expected structural performance. New economical retrofit methods should be developed and standardized. Technology developed for the seismic retrofit of these essential facilities can be transferred later to commercial and industrial facilities.Since a large number of deaths in the Bhuj earthquake took place due to collapse of schools and hospitals, it is most important to implement a specific program of seismic retrofitting and strengthening of all the schools and hospitals in quake-prone areas. It is necessary to prepare earthquake resistant designs for all the existing schools and hospitals, and implement it under expert guidance. It will require a large-scale engineering effort. The program may benefit greatly from the experiences of seismic strengthening and retrofitting of school buildings and hospitals in other countries. A lot of new technology and building designs have evolved in Japan, New Zealand and the US for earthquake-resistant buildings, including extensive use of shear walls to take lateral loads. All of them should necessarily be incorporated in all our future designs to ensure better protections. 5.9. Critical Infrastructure ProtectionThe Gujarat State Electricity Board (GSEB), which has suffered damage of US$75 million is now considering quake-resistant designs of control rooms, sub-stations and other structures housing key equipment at different locations in the state. According to the GSEB, it will adopt designs suggested by the Power Grid Corporation Limited (PGCL) and the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) for their key installations. The GSEB is also looking for possible sources to finance its quake resistant construction. Kandla port has been hit repeatedly by natural disasters. Gujarat has some 40 ports including India's busiest at Kandla - which was affected by the earthquake. Kandla handles most of India's shipping with the Middle East and Africa. These ports face a serious hazard of cyclones too. None of these ports has insurance cover. According to officials, the premium charged by the insurance companies on ports is so high that it does not make economic sense to purchase insurance , especially since these disasters normally occur only once in about 50 years. After the earthquake, the experts from the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras have visited Kandla port for damage assessment. They will provide structural solutions for retrofitting and future loss reduction. The

Bhuj airport was seriously damaged and the air traffic control tower

came down in the earthquake. The Indian Air Force made it operational

the same day by setting up a makeshift control tower facility. There

were long cracks on major highways, and water supply schemes were

rendered completely dysfunctional.

A rehabilitation program on the scale that is being planned in Gujarat provides a great opportunity for supporting all the initiatives mentioned above. These initiatives can be implemented at the national as well as state level. However, it will require resources, planning, and an implementation strategy. It also requires collaborative programs across agencies and institutions within the country and abroad. It will be necessary to support the Government of Gujarat in planning and implementing all the activities. A successful implementation of the above-mentioned activities in Gujarat will demonstrate the importance of disaster management and mitigation planning for all the developing countries. View Photos from the Reconnaissance Mission Bilham,

Roger. 1998. Slip parameters for the Rann of Kachchh, India, 16

June 1819 earthquake, quantified from contemporary accounts. Available

on Bhatia, S.C., Ravi Kumar, M. and Gupta, (Year not specified). H.K. A Probabilistic Hazard Map of India and Adjoining Regions. GSHAP. Available on http://seismo.ethz.ch/gshap/ict/india.html. Goyal,

Alok, Sinha, Ravi, Chaudhari, Madhusudan, Jaiswal, Kishor. 2001.

Preliminary Report on Damage to R/C Structures in Urban Areas of

Ahmedabad & Bhuj Khattri, K.N., Rogers, A.M., Perkins, D.M. and Algermissen, S.T., 1984. A seismic hazard map of India and adjacent areas. Tectonophysics, 108: 93-134. Malik, Javed N. Sohoni, Parag S., Merh, S.S., and Karanth, R. V. 2000. Palaeoseismology And Neotectonism Of Kachchh, Western India, available on http://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/jnmalik/malikpp1.html. The Economic Times The Indian Express The

Times of India 1.

In India, those who get less than Rs. 11,000 as annual income

are considered to be below poverty line or the poor. 7.

The per capita income of Gujarat is Rs. 7,586 annually at 1992-93

prices. You can download (size: 48 kb) a PDF version of this document. (You must have a PDF viewer, and you may obtain a free copy at the Adobe Acrobat website). |

|